Industrial Authentics

Industrial Authentics

The Blom & Blom Brothers

Dear Martin, you collect, restore and sell the industrial design items from abandoned factories mainly in Eastern Germany (former DDR)… You and your brother created the label Blom & Blom. Tell me more about your common passion, background and how do you complete each other…

Ever since we were adolescents we always had a good relationship. We travelled together for half a year, and we visited each other frequently in Berlin or Amsterdam.

The reason why it is certainly not surprising we teamed up is because we are very complimentary to each other. Kamiel is the craftsman (background in Furniture-making/Photography/Video-making), and Martijn handles the business-side of things (background in Architecture and Business). We have our own qualities, and they fit together perfectly.

Dragons lamp in old production area

How did it all start with the „industrial authentics“?

The industrial ghost-towns where the objects in our collection originate from, inspired us to do what we do. Each piece coming from such unique environment is ‘breathing’ its history, and represents its amazing atmosphere. Imagine a factory abandoned instantly, untouched for more than twenty years, and taken by the hands of time. Plant and trees grow through the floors, rainfall has slowly eating through the roof, and even wildlife returns. We do our best, but actually it is indescribable.

We have developed our own way of working in our search for industrial wastelands of the former DDR. When we scout for abandoned factories it is a combination of research, and a lot of ‘driving around’. You can do some general research to find industrial areas, but eventually it just comes down to scouting for signs like old chimneys, or railway tracks. Once a site has been discovered, we track down those responsible for the property by asking around the neighbourhood, or digging through DDR archives You get yourself in the most peculiar situations, and it takes a lot of effort to actually ‘rescue’ the pieces, but in the end it’s all worth it.

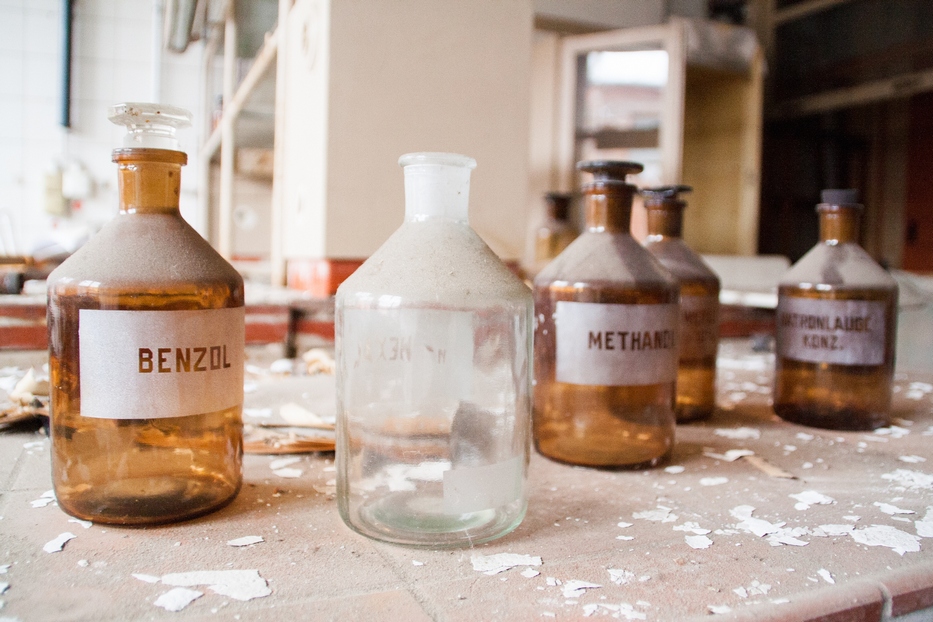

Abandoned laboratory

Have you always had an affinity for forgotten things and lost places? Did something special happen which triggered the birth of Blom & Blom?

Having lived partly Berlin, we are fascinated by the turbulent history of East Germany, and fell in love with the industrial heritage resulting from the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989. It all started with exploring abandoned industrial sites just for the fun of it. When we strolled an old laboratory, or a deserted military complex, we always had a split feeling. On one hand, there was our fascination for the amazing atmosphere of these places. On the other, our frustration that the industrial treasures they hold would ultimately end up in a dumpster.

What triggered us to set up Blom & Blom was actually a combination of common interest en our personal situations. Years ago, Kamiel left for Berlin to start an online design studio together with three Dutch friends. After being successful for almost two years, they felt the urge to start something new. As a result, they made plans for a ‘Marketplace for authentic experiences’. Plans that resulted in what is now Gidsy – a company that raised 1.2 M seed investment, and is one of the leading Berlin start-ups. Although Kamiel knew this was going to be something big, he decided to ‘resign’ from the online world in order to go back to what he has always been interested in: making stuff using his hands.

As a result his degrees in Architecture, Business, and Social sciences, Martijn pursued a career in Business. After a couple of years working in the world of suits and meetings, it appeared that also he had an urge to actually ‘produce something real’.

A phone call between the brothers in which Kamiel put forward his ideas of dropping out of his current company, and doing something which the extraordinary objects he had found during one of his photography sessions at abandoned factories, were the 15 minutes in which Blom & Blom was founded.

Your customers do not buy just an item, but a rich and epic history – presented in a passport describing its particular origin and history. You revive the industrial design items to a new life in a new environment. Which stories do they tell us? What kind of historical buildings do they come from?

We hope that our pieces can be a representation of the unique history of the places they come from. Some of our lamps come from old factories, military complexes, or deserted laboratories. These places harbor a amazing atmosphere, it is like going back in time. Imagine a factory abandoned instantly, and being untouched for more than twenty years. It kind of feels like a human society that has been taking over by nature again. Plant and even trees grow through floor, rainfall has slowly eating through ceilings, and even wildlife returns.

Do you have a favourite item, you couldn’t separate from?

The funny thing is that every month we can have a new favorite lamp. Among these is certainly our Giant Lobster lamp. It is designed to be explosion proof, and therefore has such a functional, yet sophisticated appearance. My ‘latest favorites’ are definitely the lamps we currently create from old laboratory glass. These glass beaker are for me the perfect example of an object with a hidden beauty. It is a very functional object, but if you look with a different eye, you’ll find out that the glass is very special, and that the way it has been created is only a beauty on itself. It is an object that inspires us to reuse.

Blom & Blom Workshop

Blom & Blom has an own shop, which is in fact also your workshop, a former car repair shop in Amsterdam. Did you find this place per coincidence or you searched it on purpose?

We have searched for it on purpose. We’d grown out of our father’s old shed – where we had our first workshop – and were forced to find a new home. We wanted a place where clients could visit and experience our concept completely, so we sought a location where workshop, office, and store could be in one. We found an old garage in a beautiful industrial building. In the three months of intensive renovation that followed, we brought the building back to its original atmosphere, and ideally fitted our concept. The move to this new building was also a real step forward in our business model. By styling the space completely in line with our brand principles, we created a place where people could experience our work. In the store, our products are giving the attention they deserve. The lamps are displayed separately against a white and are featured with a photo of the place we have found it. In this way, people do not only see the value of the objects, they also can catch a little bit of the adventures we get into in finding these treasures. The opening of the store was a huge success, and gave a new boost to our business, and our brand experience.

Blom & Blom Lamp at Hutspot Amsterdam

Please tell us more about your customers. Do you have walk-in customers, online customers, a small circle of regular customers?

It’s hard to really border our client group. Our clients come from all over the world, both private persons and businesses. The main thing our clients have in common, is that the are all looking for a uniques piece with its own story. This could a private person that searches a special kitchen table light, or an architect that requires a custom made light for above a restaurant bar.

Paulina’s Friends is dealing with vintage clothing, carefully collected, restored and curated on our website and in our concept store in Bikini Berlin. What do you think about this idea and the connection between art, vintage & design?

The connection between art, vintage & design certainly makes sense. They all thrive on a creative cultural feeling, and all have a large story-telling aspect.

Dear Martin, thank you very much for this interview!

Recent Comments